Process Analytics – Data Analysis for Process Audit & Improvement

Process Mining: Innovative data analysis for process optimization and audit

Step-by-Step: New ways to detect compliance violations with Process Analytics

In the course of the advancing digitization, an enormous upheaval of everyday work is currently taking place to ensure the complete recording of all steps in IT systems. In addition, companies are increasingly confronted with increasingly demanding regulatory requirements on their IT systems.

![]() Read this article in German:

Read this article in German:

“Process Mining: Innovative Analyse von Datenspuren für Audit und Forensik “

The unstoppable trend towards a connected world will further increase the possibilities of process transparency, but many processes in the company area are already covered by one or more IT systems. Each employee, as well as any automated process, leaves many data traces in IT backend systems, from which processes can be replicated retroactively or in real time. These include both obvious processes, such as the entry of a recorded purchase order or invoice, as well as partially hidden processes, such as the modification of certain entries or deletion of these business objects.

1 Understanding Process Analytics

Process Analytics is a data-driven methodology of the actual process analysis, which originates in forensics. In the wake of the increasing importance of computer crime, it became necessary to identify and analyze the data traces that potential criminals left behind in IT systems in order to reconstruct the event as much as possible.

With the trend towards Big Data Analytics, Process Analytics has not only received new data bases, but has also been further developed as an analytical method. In addition, the visualization enables the analyst or the report recipient to have a deeper understanding of even more complex business processes.

While conventional process analysis primarily involves employee interviews and monitoring of the employees at the desk in order to determine actual processes, Process Analytics is a leading method, which is purely fact-based and thus objectively approaching the processes. It is not the employees who are asked, but the IT systems, which not only store all the business objects recorded in a table-oriented manner, but also all process activities. Every IT system for enterprise purposes log all relevant activities of the whole business process, in the background and invisible to the users, such as orders, invoices or customer orders, with a time stamp.

2 The right choice of the processes to analyze

Today almost every company works with at least one ERP system. As other systems are often used, it is clear which processes can not be analyzed: Those processes, which are still carried out exclusively on paper and in the minds of the employees, which are typical decision-making processes at the strategic level and not logged in IT systems.

Operational processes, however, are generally recorded almost seamlessly in IT systems. Furthermore, almost all operational decisions are recorded by status flags in datasets.

The operational processes, which can be reconstructed and analyzed with Process Mining very well and which are of equal interest from the point of view of compliance, include for example:

– Procurement

– Logistics / Transport

– Sales / Ordering

– Warranty / Claim Management

– Human Resource Management

Process Analytics enables the greatest possible transparency across all business processes, regardless of the sector and the department. Typical case IDs are, for example, sales order number, procurement order number, customer or material numbers.

3 Selection of relevant IT systems

In principle, every IT system used in the company should be examined with regard to the relevance for the process to be analyzed. As a rule, only the ERP system (SAP ERP or others) is relevant for the analysis of the purchasing processes. However, for other process areas there might be other IT systems interesting too, for example separate accounting systems, a CRM or a MES system, which must then also be included.

Occasionally, external data should also be integrated if they provide important process information from externally stored data sources – for example, data from logistics partners.

4 Data Preparation

Before the start of the data-driven process analysis, the data directly or indirectly indicating process activities must be identified, extracted and processed in the data sources. The data are stored in database tables and server logs and are collected via a data warehousing procedure and converted into a process protocol or – also called – event log.

The event log is usually a very large and wide table which, in addition to the actual process activities, also contains parameters which can be used to filter cases and activities. The benefit of this filter option is, for example, to show only process flows where special product groups, prices, quantities, volumes, departments or employee groups are involved.

5 Analysis Execution

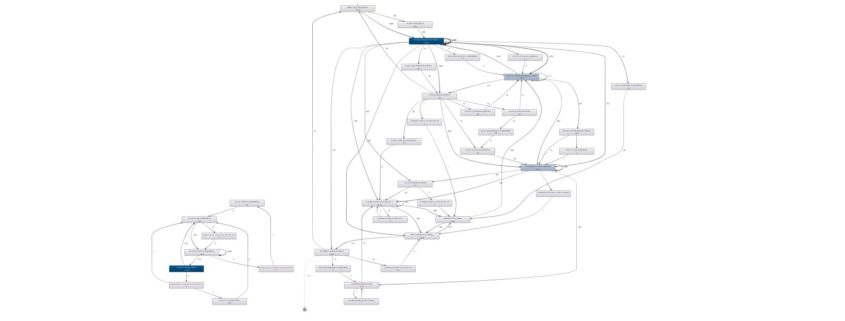

The actual inspection is done visually and thus intuitively with an interactive process flow diagram, which represents the actual processes as they could be extracted from the IT systems. The event log generated by the data preparation is loaded into a data visualization software (e.g. Celonis PM Software), which displays this log by using the case IDs and time stamps and transforms this information in a graphical process network. The process flows are therefore not modeled by human “process thinkers”, as is the case with the target processes, but show the real process flows given by the IT systems. Process Mining means, that our enterprise databases “talk” about their view of the process.

The process flows are visualized and statistically evaluated so that concrete statements can be made about the process performance and risk estimations relevant to compliance.

6 Deviation from target processes

The possibility of intuitive filtering of the process presentation also enables an analysis of all deviation of our real process from the desired target process sequences.

The deviation of the actual processes from the target processes is usually underestimated even by IT-affine managers – with Process Analytics all deviations and the general process complexity can now be investigated.

6 Detection of process control violations

The implementation of process controls is an integral part of a professional internal control system (ICS), but the actual observance of these controls is often not proven. Process Analytics allows circumventing the dual control principle or the detection of functional separation conflicts. In addition, the deliberate removal of internal control mechanisms by executives or the incorrect configuration of the IT systems are clearly visible.

7 Detection of previously unknown behavioral patterns

After checking compliance with existing controls, Process Analytics continues to be used to recognize previously unknown patterns in process networks, which point to risks or even concrete fraud cases and are not detected by any control due to their previously unknown nature. In particular, the complexity of everyday process interlacing, which is often underestimated as already mentioned, only reveals fraud scenarios that would previously not have been conceivable.

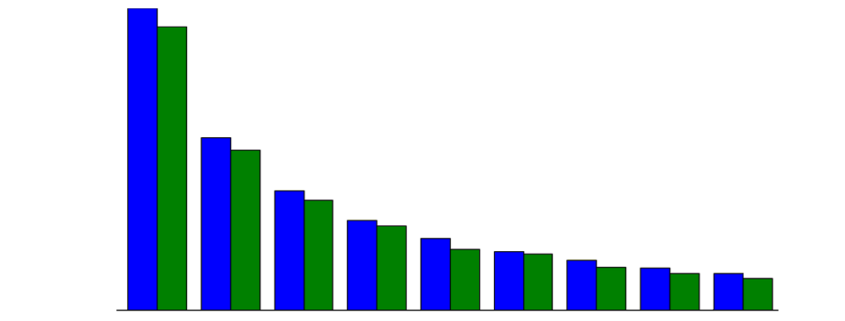

8 Reporting – also possible in real time

As a highly effective audit analysis, Process Analytics is already an iterative test at intervals of three to twelve months. After the initial implementation, compliance violations, weak or even ineffective controls, and even cases of fraud, are detected reliably. The findings can be used in the aftermath to stop the weaknesses. A further implementation of the analysis after a waiting period makes it possible to assess the effectiveness of the measures taken.

In some application scenarios, the seamless integration of the process analysis with the visual dashboard to the IT system landscape is recommended so that processes can be monitored in near real-time. This connection can also be supplemented by notification systems, so that decision makers and auditors are automatically informed about the latest process bottlenecks or violations via SMS or e-mail.

Fazit

Process Analytics is, in the course of the digitalization, the highly effective methodology from the area of Big Data Analysis for detecting compliance-relevant events throughout the company and also providing visual support for forensic data analysis. Since this is a method, and not a software, an expansion of the IT system landscape, especially for entry, is not absolutely necessary, but can be carried out by internal or external employees at regular intervals.