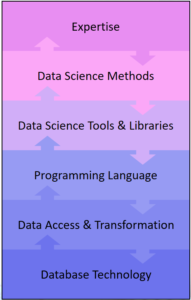

What must a Data Scientist be able to do? Which skills does as Data Scientist need to have? This question has often been asked and frequently answered by several Data Science Experts. In fact, it is now quite clear what kind of problems a Data Scientist should be able to solve and which skills are necessary for that. I would like to try to bring this consensus into a visual graph: a layer model, similar to the OSI layer model (which any data scientist should know too, by the way).

What must a Data Scientist be able to do? Which skills does as Data Scientist need to have? This question has often been asked and frequently answered by several Data Science Experts. In fact, it is now quite clear what kind of problems a Data Scientist should be able to solve and which skills are necessary for that. I would like to try to bring this consensus into a visual graph: a layer model, similar to the OSI layer model (which any data scientist should know too, by the way).

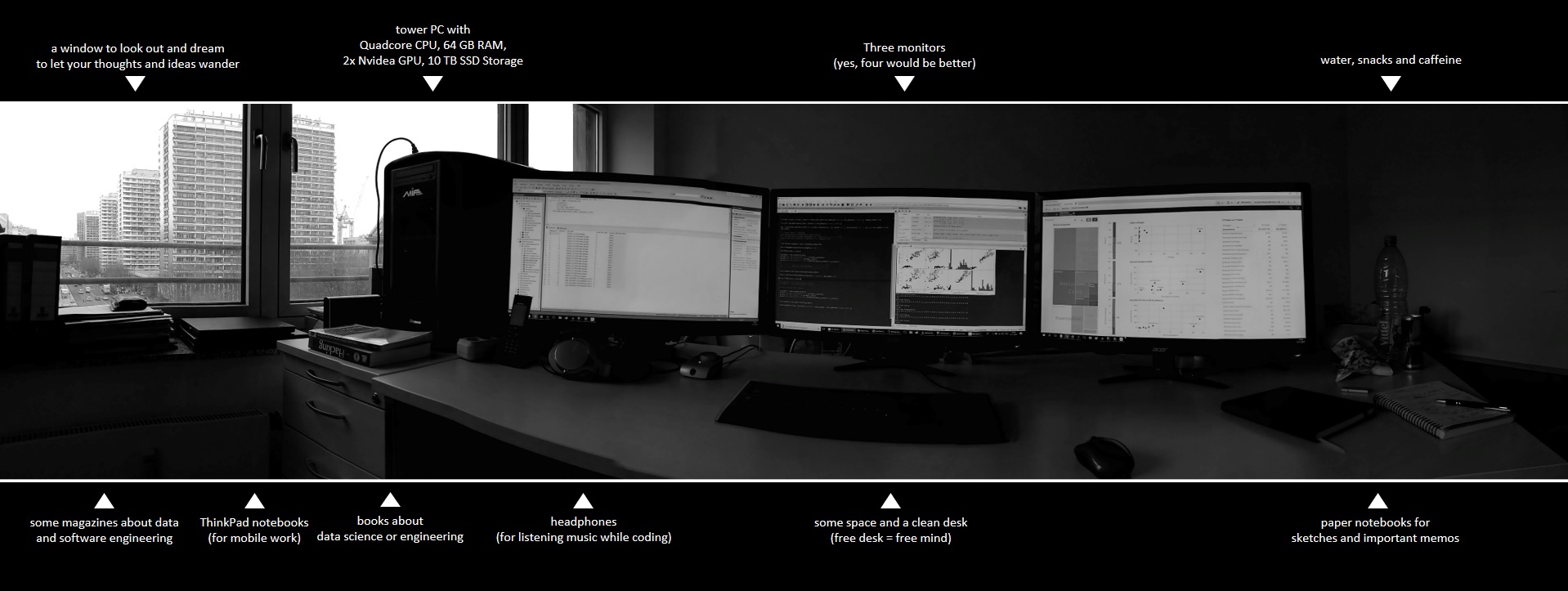

I’m giving introductory seminars in Data Science for merchants and engineers and in those seminars I always start explaining what we need to work out together in theory and practice-oriented exercises. Against this background, I came up with the idea for this layer model. Because with my seminars the problem already starts: I am giving seminars for Data Science for Business Analytics with Python. So not for medical analyzes and not with R or Julia. So I do not give a general knowledge of Data Science, but a very specific direction.

A Data Scientist must deal with problems at different levels in any Data Science project, for example, the data access does not work as planned or the data has a different structure than expected. A Data Scientist can spend hours debating its own source code or learning the ropes of new DataScience packages for its chosen programming language. Also, the right algorithms for data evaluation must be selected, properly parameterized and tested, sometimes it turns out that the selected methods were not the optimal ones. Ultimately, we are not doing Data Science all day for fun, but for generating value for a department and a data scientist is also faced with special challenges at this level, at least a basic knowledge of the expertise of that department is a must have.

Read this article in German:

Read this article in German:

“Data Science Knowledge Stack – Was ein Data Scientist können muss“

Data Science Knowledge Stack

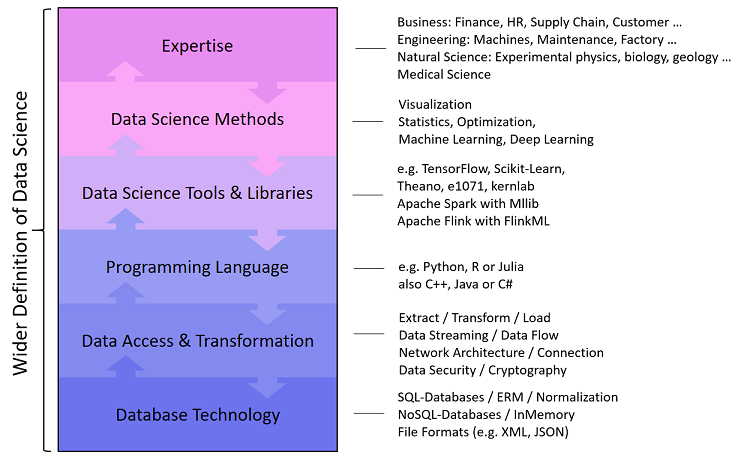

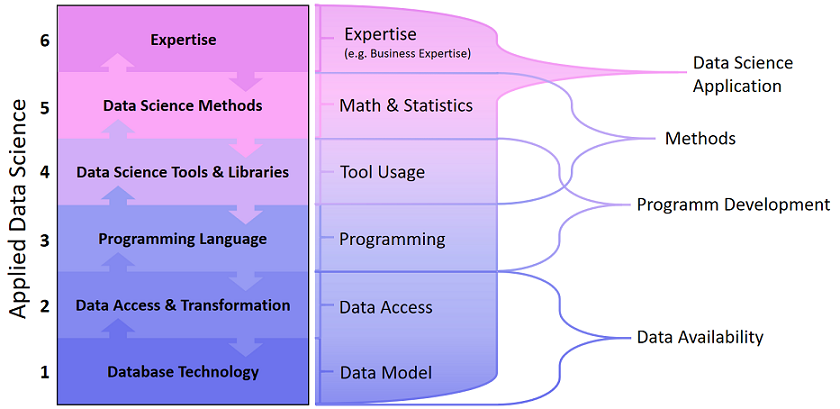

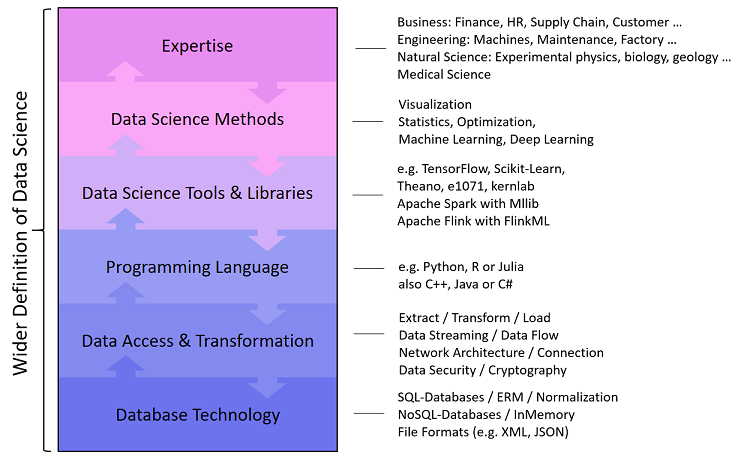

With the Data Science Knowledge Stack, I would like to provide a structured insight into the tasks and challenges a Data Scientist has to face. The layers of the stack also represent a bidirectional flow from top to bottom and from bottom to top, because Data Science as a discipline is also bidirectional: we try to answer questions with data, or we look at the potentials in the data to answer previously unsolicited questions.

The DataScience Knowledge Stack consists of six layers:

Database Technology Knowledge

A Data Scientist works with data which is rarely directly structured in a CSV file, but usually in one or more databases that are subject to their own rules. In particular, business data, for example from the ERP or CRM system, are available in relational databases, often from Microsoft, Oracle, SAP or an open source alternative. A good Data Scientist is not only familiar with Structured Query Language (SQL), but is also aware of the importance of relational linked data models, so he also knows the principle of data table normalization.

Other types of databases, so-called NoSQL databases (Not only SQL) are based on file formats, column or graph orientation, such as MongoDB, Cassandra or GraphDB. Some of these databases use their own programming languages (for example JavaScript at MongoDB or the graph-oriented database Neo4J has its own language called Cypher). Some of these databases provide alternative access via SQL (such as Hive for Hadoop).

A data scientist has to cope with different database systems and has to master at least SQL – the quasi-standard for data processing.

Data Access & Transformation Knowledge

If data are given in a database, Data Scientists can perform simple (and not so simple) analyzes directly on the database. But how do we get the data into our special analysis tools? To do this, a Data Scientist must know how to export data from the database. For one-time actions, an export can be a CSV file, but which separators and text qualifiers should be used? Possibly, the export is too large, so the file must be split.

If there is a direct and synchronous data connection between the analysis tool and the database, interfaces like REST, ODBC or JDBC come into play. Sometimes a socket connection must also be established and the principle of a client-server architecture should be known. Synchronous and asynchronous encryption methods should also be familiar to a Data Scientist, as confidential data are often used, and a minimum level of security is most important for business applications.

Many datasets are not structured in a database but are so-called unstructured or semi-structured data from documents or from Internet sources. And again we have interfaces, a frequent entry point for Data Scientists is, for example, the Twitter API. Sometimes we want to stream data in near real-time, let it be machine data or social media messages. This can be quite demanding, so the data streaming is almost a discipline with which a Data Scientist can come into contact quickly.

Programming Language Knowledge

Programming languages are tools for Data Scientists to process data and automate processing. Data Scientists are usually no real software developers and they do not have to worry about software security or economy. However, a certain basic knowledge about software architectures often helps because some Data Science programs can be going to be integrated into an IT landscape of the company. The understanding of object-oriented programming and the good knowledge of the syntax of the selected programming languages are essential, especially since not every programming language is the most useful for all projects.

At the level of the programming language, there is already a lot of snares in the programming language that are based on the programming language itself, as each has its own faults and details determine whether an analysis is done correctly or incorrectly: for example, whether data objects are copied or linked as reference, or how NULL/NaN values are treated.

Data Science Tool & Library Knowledge

Once a data scientist has loaded the data into his favorite tool, for example, one of IBM, SAS or an open source alternative such as Octave, the core work just began. However, these tools are not self-explanatory and therefore there is a wide range of certification options for various Data Science tools. Many (if not most) Data Scientists work mostly directly with a programming language, but this alone is not enough to effectively perform statistical data analysis or machine learning: We use Data Science libraries (packages) that provide data structures and methods as a groundwork and thus extend the programming language to a real Data Science toolset. Such a library, for example Scikit-Learn for Python, is a collection of methods implemented in the programming language. The use of such libraries, however, is intended to be learned and therefore requires familiarization and practical experience for reliable application.

When it comes to Big Data Analytics, the analysis of particularly large data, we enter the field of Distributed Computing. Tools (frameworks) such as Apache Hadoop, Apache Spark or Apache Flink allows us to process and analyze data in parallel on multiple servers. These tools also provide their own libraries for machine learning, such as Mahout, MLlib and FlinkML.

Data Science Method Knowledge

A Data Scientist is not simply an operator of tools, he uses the tools to apply his analysis methods to data he has selected for to reach the project targets. These analysis methods are, for example, descriptive statistics, estimation methods or hypothesis tests. Somewhat more mathematical are methods of machine learning for data mining, such as clustering or dimensional reduction, or more toward automated decision making through classification or regression.

Machine learning methods generally do not work immediately, they have to be improved using optimization methods like the gradient method. A Data Scientist must be able to detect under- and overfitting, and he must prove that the prediction results for the planned deployment are accurate enough.

Special applications require special knowledge, which applies, for example, to the fields of image recognition (Visual Computing) or the processing of human language (Natural Language Processiong). At this point, we open the door to deep learning.

Expertise

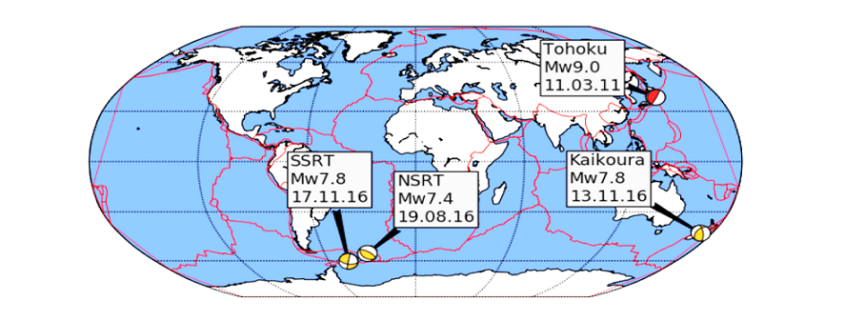

Data Science is not an end in itself, but a discipline that would like to answer questions from other expertise fields with data. For this reason, Data Science is very diverse. Business economists need data scientists to analyze financial transactions, for example, to identify fraud scenarios or to better understand customer needs, or to optimize supply chains. Natural scientists such as geologists, biologists or experimental physicists also use Data Science to make their observations with the aim of gaining knowledge. Engineers want to better understand the situation and relationships between machinery or vehicles, and medical professionals are interested in better diagnostics and medication for their patients.

In order to support a specific department with his / her knowledge of data, tools and analysis methods, every data scientist needs a minimum of the appropriate skills. Anyone who wants to make analyzes for buyers, engineers, natural scientists, physicians, lawyers or other interested parties must also be able to understand the people’s profession.

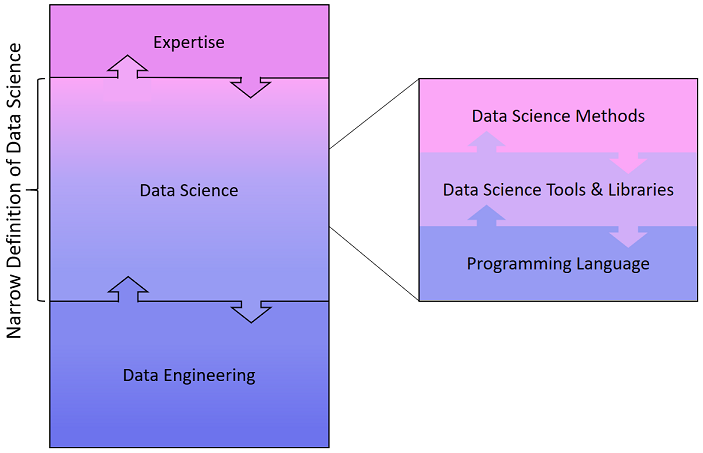

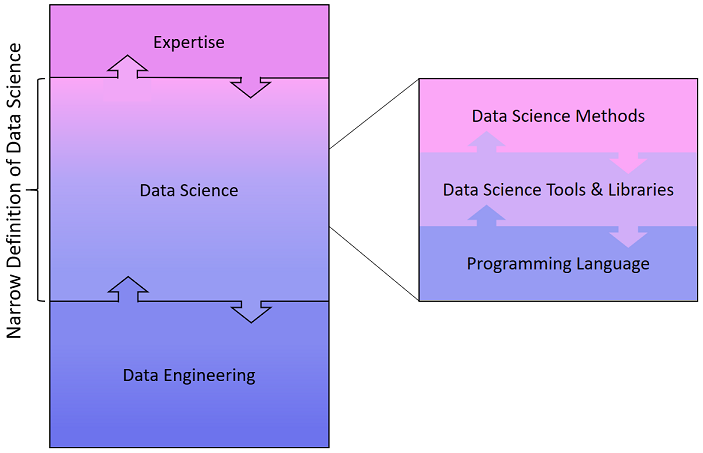

Engere Data Science Definition

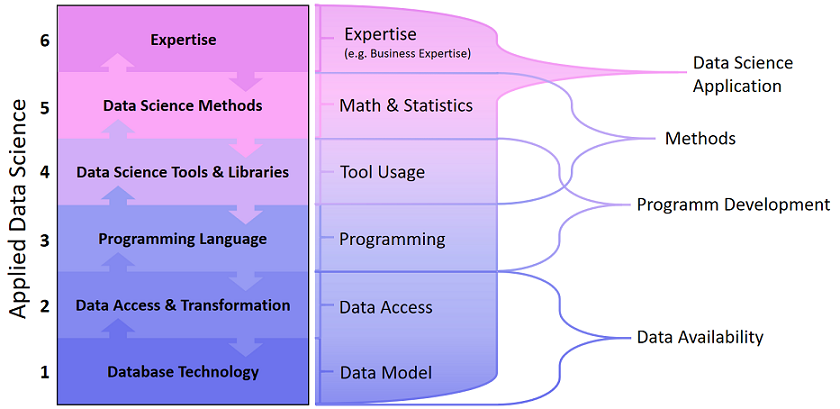

While the Data Science pioneers have long established and highly specialized teams, smaller companies are still looking for the Data Science Allrounder, which can take over the full range of tasks from the access to the database to the implementation of the analytical application. However, companies with specialized data experts have long since distinguished Data Scientists, Data Engineers and Business Analysts. Therefore, the definition of Data Science and the delineation of the abilities that a data scientist should have, varies between a broader and a more narrow demarcation.

A closer look at the more narrow definition shows, that a Data Engineer takes over the data allocation, the Data Scientist loads it into his tools and runs the data analysis together with the colleagues from the department. According to this, a Data Scientist would need no knowledge of databases or APIs, neither an expertise would be necessary …

In my experience, DataScience is not that narrow, the task spectrum covers more than just the core area. This misunderstanding comes from Data Science courses and – for me – I should point to the overall picture of Data Science again and again. In courses and seminars, which want to teach Data Science as a discipline, the focus will of course be on the core area: programming, tools and methods from mathematics & statistics.

lexoro

lexoro