A Bird’s Eye View: How Machine Learning Can Help You Charge Your E-Scooters

Bird scooters in Columbus, Ohio

Ever since I started using bike-sharing to get around in Seattle, I have become fascinated with geolocation data and the transportation sharing economy. When I saw this project leveraging the mobility data RESTful API from the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, I was eager to dive in and get my hands dirty building a data product utilizing a company’s mobility data API.

Unfortunately, the major bike and scooter providers (Bird, JUMP, Lime) don’t have publicly accessible APIs. However, some folks have seemingly been able to reverse-engineer the Bird API used to populate the maps in their Android and iOS applications.

One interesting feature of this data is the nest_id, which indicates if the Bird scooter is in a “nest” — a centralized drop-off spot for charged Birds to be released back into circulation.

I set out to ask the following questions:

- Can real-time predictions be made to determine if a scooter is currently in a nest?

- For non-nest scooters, can new nest location recommendations be generated from geospatial clustering?

To answer these questions, I built a full-stack machine learning web application, NestGenerator, which provides an automated recommendation engine for new nest locations. This application can help power Bird’s internal nest location generation that runs within their Android and iOS applications. NestGenerator also provides real-time strategic insight for Bird chargers who are enticed to optimize their scooter collection and drop-off route based on proximity to scooters and nest locations in their area.

Bird

The electric scooter market has seen substantial growth with Bird’s recent billion dollar valuation and their $300 million Series C round in the summer of 2018. Bird offers electric scooters that top out at 15 mph, cost $1 to unlock and 15 cents per minute of use. Bird scooters are in over 100 cities globally and they announced in late 2018 that they eclipsed 10 million scooter rides since their launch in 2017.

Bird scooters in Tel Aviv, Israel

With all of these scooters populating cities, there’s much-needed demand for people to charge them. Since they are electric, someone needs to charge them! A charger can earn additional income for charging the scooters at their home and releasing them back into circulation at nest locations. The base price for charging each Bird is $5.00. It goes up from there when the Birds are harder to capture.

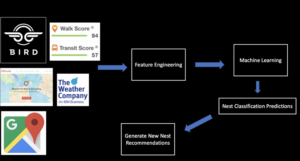

Data Collection and Machine Learning Pipeline

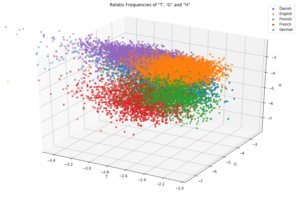

The full data pipeline for building “NestGenerator”

Data

From the details here, I was able to write a Python script that returned a list of Bird scooters within a specified area, their geolocation, unique ID, battery level and a nest ID.

I collected scooter data from four cities (Atlanta, Austin, Santa Monica, and Washington D.C.) across varying times of day over the course of four weeks. Collecting data from different cities was critical to the goal of training a machine learning model that would generalize well across cities.

Once equipped with the scooter’s latitude and longitude coordinates, I was able to leverage additional APIs and municipal data sources to get granular geolocation data to create an original scooter attribute and city feature dataset.

Data Sources:

- Walk Score API: returns a walk score, transit score and bike score for any location.

- Google Elevation API: returns elevation data for all locations on the surface of the earth.

- Google Places API: returns information about places. Places are defined within this API as establishments, geographic locations, or prominent points of interest.

- Google Reverse Geocoding API: reverse geocoding is the process of converting geographic coordinates into a human-readable address.

- Weather Company Data: returns the current weather conditions for a geolocation.

- LocationIQ: Nearby Points of Interest (PoI) API returns specified PoIs or places around a given coordinate.

- OSMnx: Python package that lets you download spatial geometries and model, project, visualize, and analyze street networks from OpenStreetMap’s APIs.

Feature Engineering

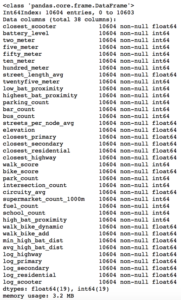

After extensive API wrangling, which included a four-week prolonged data collection phase, I was finally able to put together a diverse feature set to train machine learning models. I engineered 38 features to classify if a scooter is currently in a nest.

Full Feature Set

The features boiled down into four categories:

- Amenity-based: parks within a given radius, gas stations within a given radius, walk score, bike score

- City Network Structure: intersection count, average circuity, street length average, average streets per node, elevation level

- Distance-based: proximity to closest highway, primary road, secondary road, residential road

- Scooter-specific attributes: battery level, proximity to closest scooter, high battery level (> 90%) scooters within a given radius, total scooters within a given radius

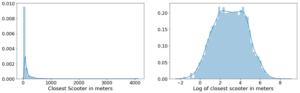

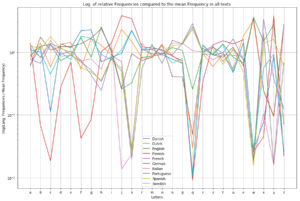

Log-Scale Transformation

For each feature, I plotted the distribution to explore the data for feature engineering opportunities. For features with a right-skewed distribution, where the mean is typically greater than the median, I applied these log transformations to normalize the distribution and reduce the variability of outlier observations. This approach was used to generate a log feature for proximity to closest scooter, closest highway, primary road, secondary road, and residential road.

An example of a log transformation

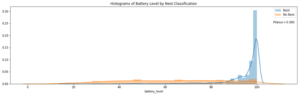

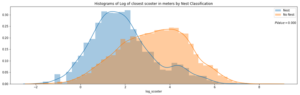

Statistical Analysis: A Systematic Approach

Next, I wanted to ensure that the features I included in my model displayed significant differences when broken up by nest classification. My thinking was that any features that did not significantly differ when stratified by nest classification would not have a meaningful predictive impact on whether a scooter was in a nest or not.

Distributions of a feature stratified by their nest classification can be tested for statistically significant differences. I used an unpaired samples t-test with a 0.01% significance level to compute a p-value and confidence interval to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in means for a feature stratified by nest classification. I rejected the null hypothesis if a p-value was smaller than the 0.01% threshold and if the 99.9% confidence interval did not straddle zero. By rejecting the null-hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis, it’s deemed there is a significant difference in means of a feature by nest classification.

Battery Level Distribution Stratified by Nest Classification to run a t-test

Log of Closest Scooter Distribution Stratified by Nest Classification to run a t-test

Throwing Away Features

Using the approach above, I removed ten features that did not display statistically significant results.

Statistically Insignificant Features Removed Before Model Development

Model Development

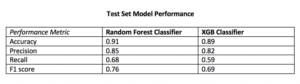

I trained two models, a random forest classifier and an extreme gradient boosting classifier since tree-based models can handle skewed data, capture important feature interactions, and provide a feature importance calculation. I trained the models on 70% of the data collected for all four cities and reserved the remaining 30% for testing.

After hyper-parameter tuning the models for performance on cross-validation data it was time to run the models on the 30% of test data set aside from the initial data collection.

I also collected additional test data from other cities (Columbus, Fort Lauderdale, San Diego) not involved in training the models. I took this step to ensure the selection of a machine learning model that would generalize well across cities. The performance of each model on the additional test data determined which model would be integrated into the application development.

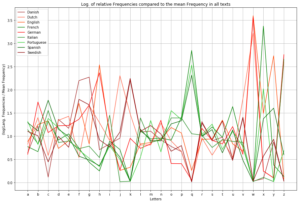

Performance on Additional Cities Test Data

The Random Forest Classifier displayed superior performance across the board

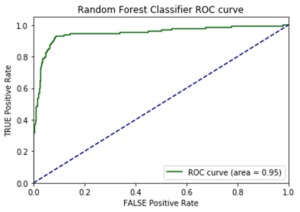

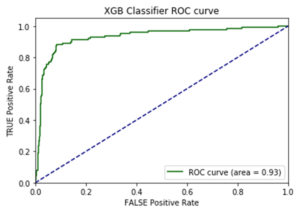

I opted to move forward with the random forest model because of its superior performance on AUC score and accuracy metrics on the additional cities test data. AUC is the Area under the ROC Curve, and it provides an aggregate measure of model performance across all possible classification thresholds.

AUC Score on Test Data for each Model

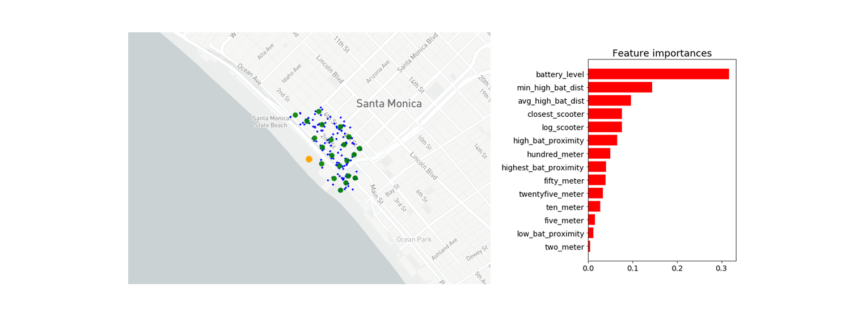

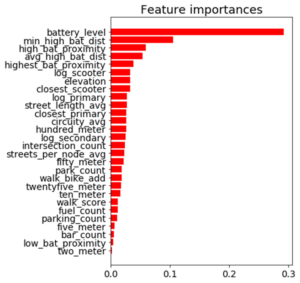

Feature Importance

Battery level dominated as the most important feature. Additional important model features were proximity to high level battery scooters, proximity to closest scooter, and average distance to high level battery scooters.

Feature Importance for the Random Forest Classifier

The Trade-off Space

Once I had a working machine learning model for nest classification, I started to build out the application using the Flask web framework written in Python. After spending a few days of writing code for the application and incorporating the trained random forest model, I had enough to test out the basic functionality. I could finally run the application locally to call the Bird API and classify scooter’s into nests in real-time! There was one huge problem, though. It took more than seven minutes to generate the predictions and populate in the application. That just wasn’t going to cut it.

The question remained: will this model deliver in a production grade environment with the goal of making real-time classifications? This is a key trade-off in production grade machine learning applications where on one end of the spectrum we’re optimizing for model performance and on the other end we’re optimizing for low latency application performance.

As I continued to test out the application’s performance, I still faced the challenge of relying on so many APIs for real-time feature generation. Due to rate-limiting constraints and daily request limits across so many external APIs, the current machine learning classifier was not feasible to incorporate into the final application.

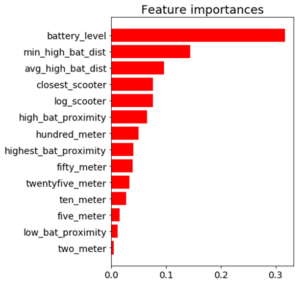

Run-Time Compliant Application Model

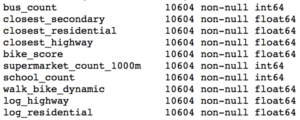

After going back to the drawing board, I trained a random forest model that relied primarily on scooter-specific features which were generated directly from the Bird API.

Through a process called vectorization, I was able to transform the geolocation distance calculations utilizing NumPy arrays which enabled batch operations on the data without writing any “for” loops. The distance calculations were applied simultaneously on the entire array of geolocations instead of looping through each individual element. The vectorization implementation optimized real-time feature engineering for distance related calculations which improved the application response time by a factor of ten.

Feature Importance for the Run-time Compliant Random Forest Classifier

This random forest model generalized well on test-data with an AUC score of 0.95 and an accuracy rate of 91%. The model retained its prediction accuracy compared to the former feature-rich model, but it gained 60x in application performance. This was a necessary trade-off for building a functional application with real-time prediction capabilities.

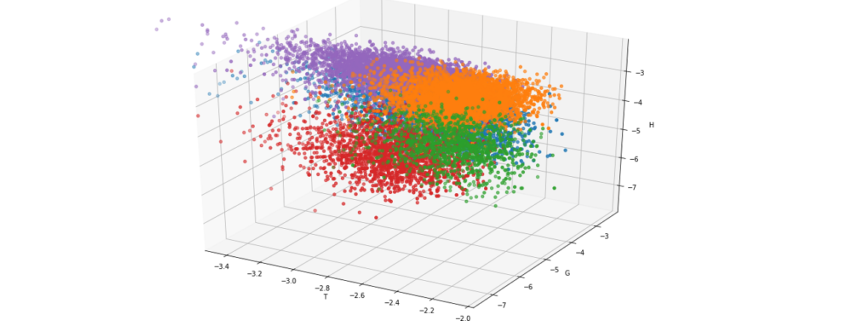

Geospatial Clustering

Now that I finally had a working machine learning model for classifying nests in a production grade environment, I could generate new nest locations for the non-nest scooters. The goal was to generate geospatial clusters based on the number of non-nest scooters in a given location.

The k-means algorithm is likely the most common clustering algorithm. However, k-means is not an optimal solution for widespread geolocation data because it minimizes variance, not geodetic distance. This can create suboptimal clustering from distortion in distance calculations at latitudes far from the equator. With this in mind, I initially set out to use the DBSCAN algorithm which clusters spatial data based on two parameters: a minimum cluster size and a physical distance from each point. There were a few issues that prevented me from moving forward with the DBSCAN algorithm.

- The DBSCAN algorithm does not allow for specifying the number of clusters, which was problematic as the goal was to generate a number of clusters as a function of non-nest scooters.

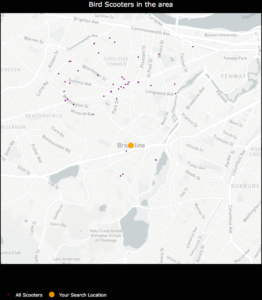

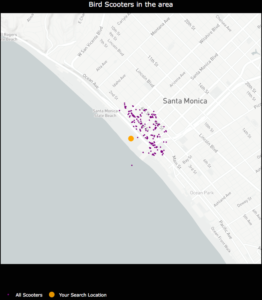

- I was unable to hone in on an optimal physical distance parameter that would dynamically change based on the Bird API data. This led to suboptimal nest locations due to a distortion in how the physical distance point was used in clustering. For example, Santa Monica, where there are ~15,000 scooters, has a higher concentration of scooters in a given area whereas Brookline, MA has a sparser set of scooter locations.

An example of how sparse scooter locations vs. highly concentrated scooter locations for a given Bird API call can create cluster distortion based on a static physical distance parameter in the DBSCAN algorithm. Left:Bird scooters in Brookline, MA. Right:Bird scooters in Santa Monica, CA.

Given the granularity of geolocation scooter data I was working with, geospatial distortion was not an issue and the k-means algorithm would work well for generating clusters. Additionally, the k-means algorithm parameters allowed for dynamically customizing the number of clusters based on the number of non-nest scooters in a given location.

Once clusters were formed with the k-means algorithm, I derived a centroid from all of the observations within a given cluster. In this case, the centroids are the mean latitude and mean longitude for the scooters within a given cluster. The centroids coordinates are then projected as the new nest recommendations.

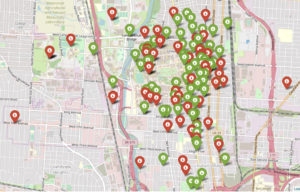

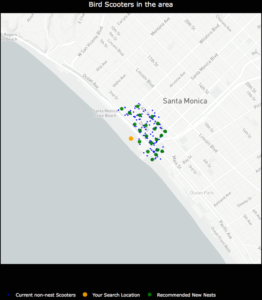

NestGenerator showcasing non-nest scooters and new nest recommendations utilizing the K-Means algorithm.

NestGenerator Application

After wrapping up the machine learning components, I shifted to building out the remaining functionality of the application. The final iteration of the application is deployed to Heroku’s cloud platform.

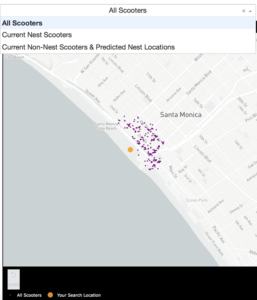

In the NestGenerator app, a user specifies a location of their choosing. This will then call the Bird API for scooters within that given location and generate all of the model features for predicting nest classification using the trained random forest model. This forms the foundation for map filtering based on nest classification. In the app, a user has the ability to filter the map based on nest classification.

Drop-Down Map View filtering based on Nest Classification

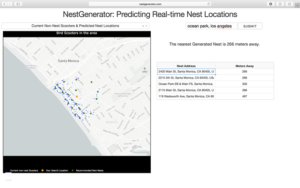

Nearest Generated Nest

To see the generated nest recommendations, a user selects the “Current Non-Nest Scooters & Predicted Nest Locations” filter which will then populate the application with these nest locations. Based on the user’s specified search location, a table is provided with the proximity of the five closest nests and an address of the Nest location to help inform a Bird charger in their decision-making.

NestGenerator web-layout with nest addresses and proximity to nearest generated nests

Conclusion

By accurately predicting nest classification and clustering non-nest scooters, NestGenerator provides an automated recommendation engine for new nest locations. For Bird, this application can help power their nest location generation that runs within their Android and iOS applications. NestGenerator also provides real-time strategic insight for Bird chargers who are enticed to optimize their scooter collection and drop-off route based on scooters and nest locations in their area.

Code

The code for this project can be found on my GitHub

Comments or Questions? Please email me an E-Mail!

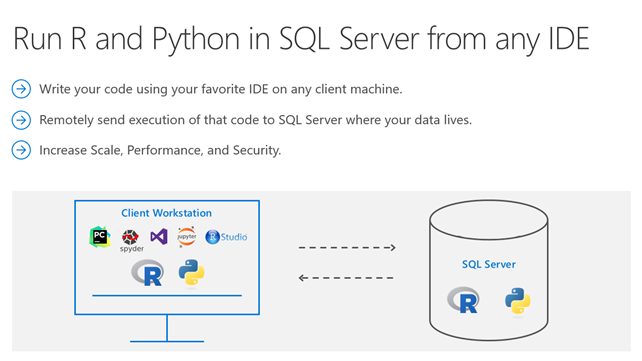

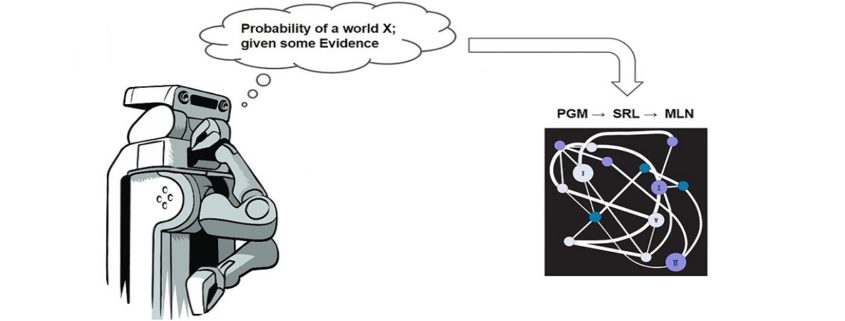

scientists, which will involve more sophisticated analysis, predictive modeling, regressions and Bayesian classification. That stuff at scale doesn’t work well on anyone’s engine right now. If you want to do complex analytics on big data, you have a big problem right now.”

scientists, which will involve more sophisticated analysis, predictive modeling, regressions and Bayesian classification. That stuff at scale doesn’t work well on anyone’s engine right now. If you want to do complex analytics on big data, you have a big problem right now.”